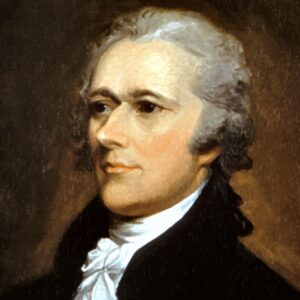

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the penname “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #9,” arguing that the sovereignty of the States will be preserved as long as their legislatures continue to elect their two Senators. In paragraph 15 he writes,

… The proposed Constitution, so far from implying an abolition of the State governments, makes them constituent parts of the national sovereignty, by allowing them a direct representation in the Senate, and leaves in their possession certain exclusive and very important portions of sovereign power. This fully corresponds, in every rational import of the terms, with the idea of a federal government.

[restored 11/29/2024]

James Madison, a former Delegate, from the Commonwealth of Virginia, to the Constitutional Convention, using the penname “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #10,” arguing that factions (special interests) are dangerous to liberty; that liberty is threatened by direct democracy and best preserved by a representative republic. In paragraphs 2, 3, 4, 5, 12, 14 and 16 he writes,

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed [sic] to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: the one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: the one, by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

… Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

· · · · · · ·

… Hence it is that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths. …

· · · · · · ·

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

· · · · · · ·

… [E]ach representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to centre [sic] in men who possess the most attractive merit and the most diffusive and established characters. [Emphasis added]

[restored 11/29/2024]

Subsequent Events:

Authority:

Articles of Confederation, Article XIII

ccc-2point0.com/Articles-of-Confederation

References:

Federalist No 9 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed9.asp

Federalist No 10 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed10.asp

Federalist No. 9 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._9

Federalist No. 10 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._10