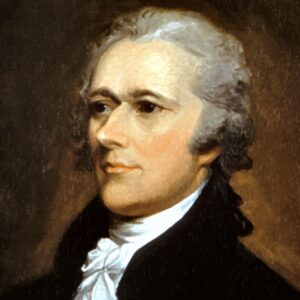

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the penname “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #78.” In paragraphs 8, 9, 11, 12 and 15 he writes,

… “[T]here is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers. …

… Limitations … can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void. …

· · · · · ·

… No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid. To deny this, would be to affirm, that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers, may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid.

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority:. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body.

· · · · · ·

It can be of no weight to say that the courts, on the pretense of a repugnancy, may substitute their own pleasure to the constitutional intentions of the legislature. … The courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise WILL instead of JUDGMENT, the consequence would equally be the substitution of their pleasure to that of the legislative body. [Emphasis added]

Question: How can federal judges objectively judge the limitations on federal powers, should that not be the prerogative of Fully Informed Juries?

[restored 12/14/2024]

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the pen name “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #80,” paragraphs 12 and 15, of which, describe the Supreme Court’s prerogative to review the constitutionality of treaties”:

It is to comprehend “all cases in law and equity arising under the Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority:. …

· · · · · · ·

The judiciary authority: of the Union is to extend. … To treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority: of the United States, and to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers, and consuls. These belong to the fourth class of the enumerated cases, as they have an evident connection with the preservation of the national peace.

[added 12/14/2024] Thanks to Bill Holmes for this entry.

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the pseudonym “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #81,” paragraph four of which claims that the proposed Constitution for the united States is NOT intended to be used by the Federal judiciary to constrain the States:

[T]here is not a syllable in the plan under consideration which directly empowers the national courts to construe the laws according to the spirit of the Constitution, or which gives them any greater latitude in this respect than may be claimed by the courts of every State. I admit, however, that the Constitution ought to be the standard of construction for the laws, and that wherever there is an evident opposition, the laws ought to give place to the Constitution.

[added 12/14/2024] Thanks to Jim Lorenz for this entry.

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the pen name “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #82,” paragraph five of which, denies that the proposed Constitution is intended to give the power of judicial review to the courts:

In the first place, there is not a syllable in the plan under consideration which DIRECTLY empowers the national courts to construe the laws according to the spirit of the Constitution, or which gives them any greater latitude in this respect than may be claimed by the courts of every State. I admit, however, that the Constitution ought to be the standard of construction for the laws, and that wherever there is an evident opposition, the laws ought to give place to the Constitution. But this doctrine is not deducible from any circumstance peculiar to the plan of the convention, but from the general theory of a limited Constitution; and as far as it is true, is equally applicable to most, if not to all the State governments. [Emphasis in the original]

NOTE: It is the duty of Fully Informed Juries to thwart unconstitutional statutes.

[added 12/14/2024] Thanks to Bill Holmes for this entry.

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the pen name “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #83,” paragraphs 11 through 13, of which, praise the institution of Trial by a Fully Informed Jury as the most essential ingredient to preserving liberty—even greater than that of a strong Militia:

The friends and adversaries of the plan of the convention, if they agree in nothing else, concur at least in the value they set upon the [T]rial by [J]ury; or if there is any difference between them it consists in this: the former regard it as a valuable safeguard to liberty; the latter represent it as the very palladium of free government. For my own part, the more the operation of the institution has fallen under my observation, the more reason I have discovered for holding it in high estimation; and it would be altogether superfluous to examine to what extent it deserves to be esteemed useful or essential in a representative republic, or how much more merit it may be entitled to, as a defense against the oppressions of an hereditary monarch, than as a barrier to the tyranny of popular magistrates in a popular government. … Arbitrary impeachments, arbitrary methods of prosecuting pretended offenses, and arbitrary punishments upon arbitrary convictions, have ever appeared to me to be the great engines of judicial despotism; and these have all relation to criminal proceedings. The [T]rial by [J]ury in criminal cases, aided by the habeas-corpus act, seems therefore to be alone concerned in the question. And both of these are provided for, in the most ample manner, in the plan of the convention. [Emphasis added]

· · · · · · ·

It has been observed, that [T]rial by [J]ury is a safeguard against an oppressive exercise of the power of taxation. This observation deserves to be canvassed.

· · · · · · ·

It is evident that it can have no influence upon the legislature, in regard to the AMOUNT of taxes to be laid, to the OBJECTS upon which they are to be imposed, or to the RULE by which they are to be apportioned. If it can have any influence, therefore, it must be upon the mode of collection, and the conduct of the officers intrusted [sic] with the execution of the revenue laws. [Emphasis in the original]

Question: In paragraph number 12, Hamilton discusses the historical fact that “[T]rial by [J]ury is a safeguard against an oppressive exercise of the power of taxation,” how can a modern day jury act as a safeguard against oppressive taxation if it is only to judge the facts, and not the statute in question? Does it not seem then that the framers and ratifiers were Camdenites, and believed in the prerogative of the Jury to judge the law, as well as the facts?

[added 12/14/2024] Thanks to Bill Holmes for this entry.

Alexander Hamilton, a former Delegate, from New York, to the Constitutional Convention, using the pen name “Publius,” publishes “Federalist #84,” paragraph nine of which, explains the danger in adding a “Bill of Rights” to the proposed Constitution, as it would imply the denial of rights that are not mentioned:

I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed?

And in paragraphs four and five it is pointed out that the greater protections of prohibitions against Bills of Attainder (pronouncement of guilt by a legislative body), ex post facto laws (statutes that take effect before they are enacted), and Titles of Nobility, do not exist in the Articles of Confederation, but do exist in the proposed Constitution for the united States. Hamilton also warns in paragraph nine that adding a “Bill of Rights” could be dangerous because Congress might try to do things that the Constitution does not say it may not do:

… The establishment of the writ of habeas corpus, the prohibition of ex-post-facto laws, and of TITLES OF NOBILITY, TO WHICH WE HAVE NO CORRESPONDING PROVISION IN OUR CONSTITUTION [the Articles of Confederation], are perhaps greater securities to liberty and republicanism than any it contains. The creation of crimes after the commission of the fact, or, in other words, the subjecting of men to punishment for things which, when they were done, were breaches of no law, and the practice of arbitrary imprisonments, have been, in all ages, the favorite and most formidable instruments of tyranny. The observations of the judicious Blackstone, in reference to the latter, are well worthy of recital: “To bereave a man of life, ‘says he,’ or by violence to confiscate his estate, without accusation or trial, would be so gross and notorious an act of despotism, as must at once convey the alarm of tyranny throughout the whole nation; but confinement of the person, by secretly hurrying him to jail, where his sufferings are unknown or forgotten, is a less public, a less striking, and therefore A MORE DANGEROUS ENGINE of arbitrary government.” And as a remedy for this fatal evil he is everywhere peculiarly emphatical [sic] in his encomiums on the habeas-corpus act, which in one place he calls “the BULWARK of the British Constitution.” (Emphasis in the original)

· · · · · · ·

Nothing need be said to illustrate the importance of the prohibition of titles of nobility. This may truly be denominated the cornerstone of republican government; for so long as they are excluded, there can never be serious danger that the government will be any other than that of the people.

· · · · · · ·

I go further and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power. They might urge with a semblance of reason, that the Constitution ought not to be charged with the absurdity of providing against the abuse of an authority: which was not given, and that the provision against restraining the liberty of the press afforded a clear implication, that a power to prescribe proper regulations concerning it was intended to be vested in the national government. This may serve as a specimen of the numerous handles which would be given to the doctrine of constructive powers, by the indulgence of an injudicious zeal for bills of rights.

[updated 12/14/2024]

Lawyer Hamilton was conflicted. It was he who pushed the unconstitutional national bank bill on George Washington, who approved of it, in spite of the fact that no power to establish such a central bank exists in the Constitution, then or now, yet the evil precedent was established. Hamilton might have had a good legal argument as Expressio unius est exclusio alterius (Expression of the one is exclusion of the other: a principle in law: when one or more things of a class are expressly mentioned others of the same class are excluded.) is a well known principle. However, many people, including lawyers, often include the excluded in last wills & testaments, by mentioning them and awarding them $1.00, so they can’t say the testator was feeble of mind and merely forgot the ‘favorite’ nephew/niece, etc.

In light of our experience with the government’s lack of observance of Constitutional exclusions, the Bill of Rights was a very good idea, and needs to be expanded. –– JL

Subsequent Events:

Authority:

Articles of Confederation, Article XIII

ccc-2point0.com/Articles-of-Confederation

References:

Don Erik Franzen, “Lest Ye Be Judged,” Reason, March 1998, 11.

Gary M. Galles, “Bill of Rights Wasn’t a Slam Dunk,” Orange County (California) Register, 15 December 2005, Local:8.

Federalist No. 78 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed78.asp

Federalist No 80 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed80.asp

Federalist No 82 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed82.asp

Federalist No 83 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed83.asp

Federalist No. 84 – The Avalon Project

avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed84.asp

Federalist No. 78 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._78

Federalist No. 80 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._80

Federalist No. 82 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._82

Federalist No. 83 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._83

Federalist No. 84 – Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federalist_No._84

Nullification Revisited

campaignforliberty.com/article.php?view=57”www.campaignforliberty.com/article.php?view=57